If there’s one skill that I feel like I’ve truly learned throughout my years as a product manager, it’s the art and science of decision-making.

As product people, we make hundreds of decisions every day. Mastering how to make good decisions is the single biggest lever we can pull to maximize our impact.

There are already many great decision-making frameworks out there on the internet, so that won’t be my focus today. Instead, I want to take a step back to discuss an even more fundamental question — what is a good decision?

You might think the answer is obvious, but is it really? Let’s have a closer look.

Good decision vs. bad decision

Most people judge the quality of a decision by the outcome it produces. However, that metric is not as straightforward as it seems. While the latter is the end goal of the former, they are actually two different things.

“Huh? But it’s the outcome that matters, right?”

Well, yes and no.

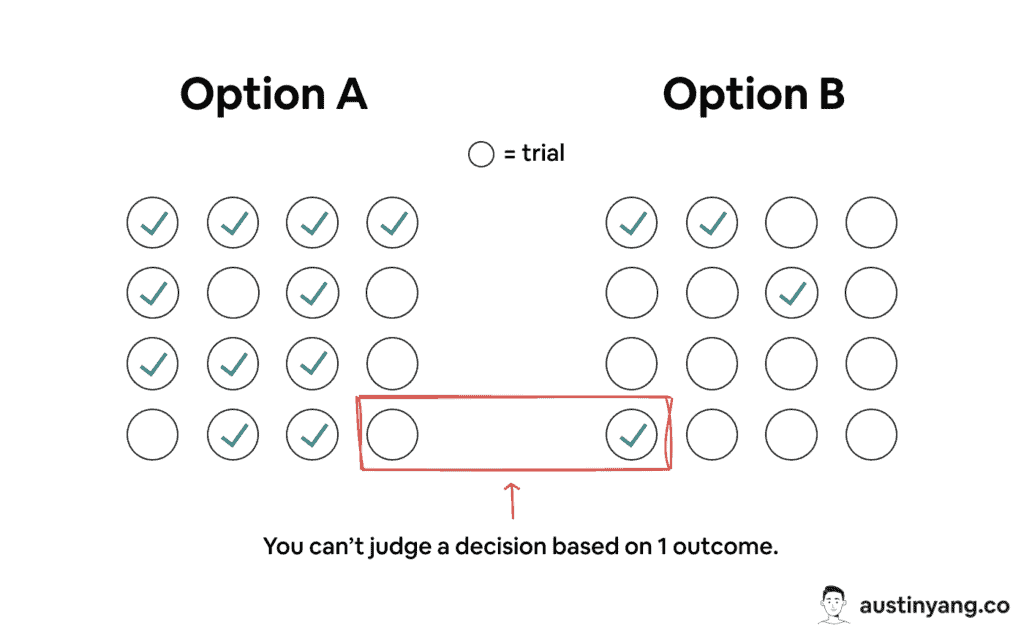

Decision-making is about choosing a path with the highest “chance” of success based on the information available. However, nothing in life is guaranteed.

Even if you have years of quality data, thousands of statistically significant A/B test results, and industry-leading domain knowledge, your decision might still lead to a disappointing outcome due to pure bad luck.

The opposite can also be true. Even if you make an illogical decision based on zero research or prior knowledge, luck could still be on your side.

“But if the outcome is good, why does it matter how the decision was made?”

It doesn’t…if that’s the only decision you are ever going to make. But we don’t ever make just one decision. We make thousands of decisions that build on top of one another.

If you attribute a single success to the decision-making process (or the person making the decision), you will try to follow the same formula again. Chances are you won’t get so lucky the next time around. Time and time again, I have seen that “lucky” bad decisions cause way more harm down the road for this precise reason.

To be clear, I’m not saying that outcomes don’t matter. If your decisions are as good as you believe they are, their quality should reflect on the outcomes, given a sufficient sample size.

A good analogy here is 3-point shots in basketball:

In the NBA, the most elite shooters can make around 40% of their 3-point attempts, whereas players who shoot below 33% are generally considered bad shooters.

In one game, this difference might not seem huge, but it makes a world of difference over the stretch of a season. If you are a coach, you wouldn’t want to assign your plays based on just one game of performance.

However, unlike basketball, there are no definitive criteria to judge the outcome of a business decision. In fact, it is extremely hard for a few reasons…

The objective is never truly set

We all know that before a decision can be made, an objective must first be set. Unfortunately, it is never that easy in reality.

For example, let’s say you are part of a team in charge of pricing redesign, and everyone agrees on the goal of maximizing user growth. The most logical option here is to make the product free, as nothing attracts more users than a free product. However, if anyone dares to propose this, it will certainly be met with “Hmm, but we still have to consider revenue.”

“Okay, how much?”

“Uh…ideally as much as possible. The main goal is still user growth, though.”

“So you’re saying 100% user growth + 10% revenue growth will be better than 80% user growth + 5X revenue growth?”

“Well, no, in this case outcome two is better. I guess we have to compare the options to see.”

As you can see, an objective is a decision within a decision, and it often must be considered together with the options. This non-linear process creates a paradox: How do you evaluate the outcome when the criteria are moving at the same time?

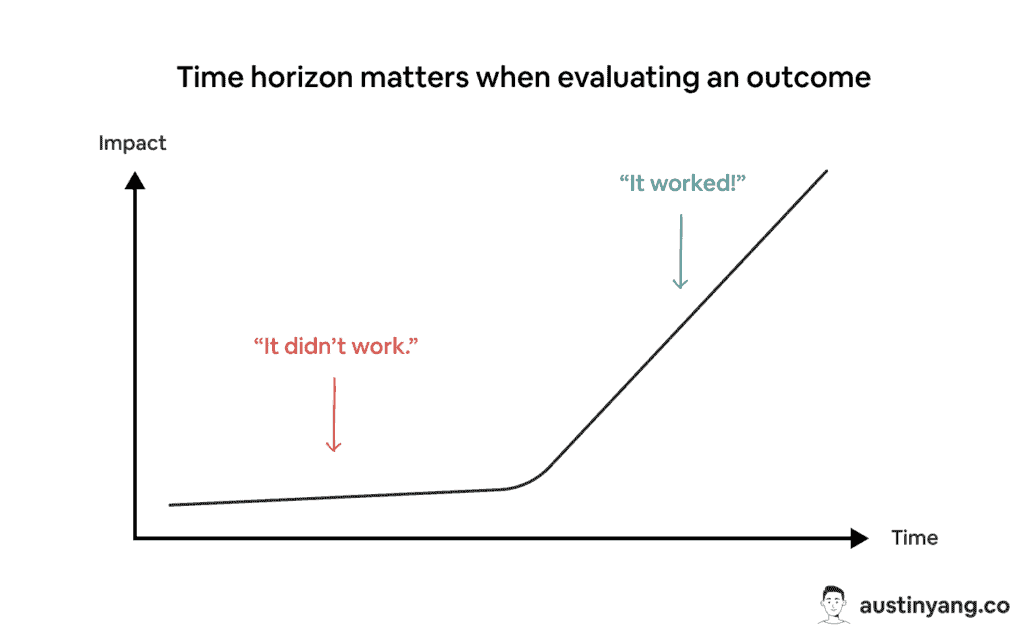

The time horizon matters

Depending on the time horizon you look at, you can reach very different conclusions about whether your decision was a success.

If you make an investment expecting long-term return, its short-term performance does not matter. If your decision aims to get quick wins, don’t expect it to be a difference-maker in the long run.

This idea is not hard to understand, but it is hard to adopt in practice for two reasons:

First, it’s difficult to estimate the timeframe. How do you accurately define what “long-term” or “short-term” means in each case?

- To a startup, one year might sound like an eternity.

- To a big corporate, one year is a short chapter.

- To a company working on a market-changing product (e.g., AI, space tech, autonomous cars), one year is merely a paragraph in the long book of history.

Second, everyone says that they play the long game, but it is often not true.

- Company leaders who craft a five-year plan change course as soon as a quarterly target is missed.

- VCs who claim to invest in the future stop cutting checks as soon as there is a sign of an economic downturn.

- Financial-literate investors worry about day-to-day stock performance even though data shows that “time in the market” will always beat “timing the market” after a long enough period.

This tendency of valuing short-term results isn’t irrational. The longer we wait for an outcome, the riskier it gets. How many startups have the patience like Figma to bet on R&D for five years with no revenue? Out of those startups, how many made the right bets? How many individuals making those decisions have incentives to care about long-term outcomes?

Unfortunately, the most important topics in business, such as retention and brand, will always be a long-term play. Many companies fail precisely because they keep optimizing for short-term outcomes, which prevents them from investing in the long term or creates path dependence that cannot be reverted.

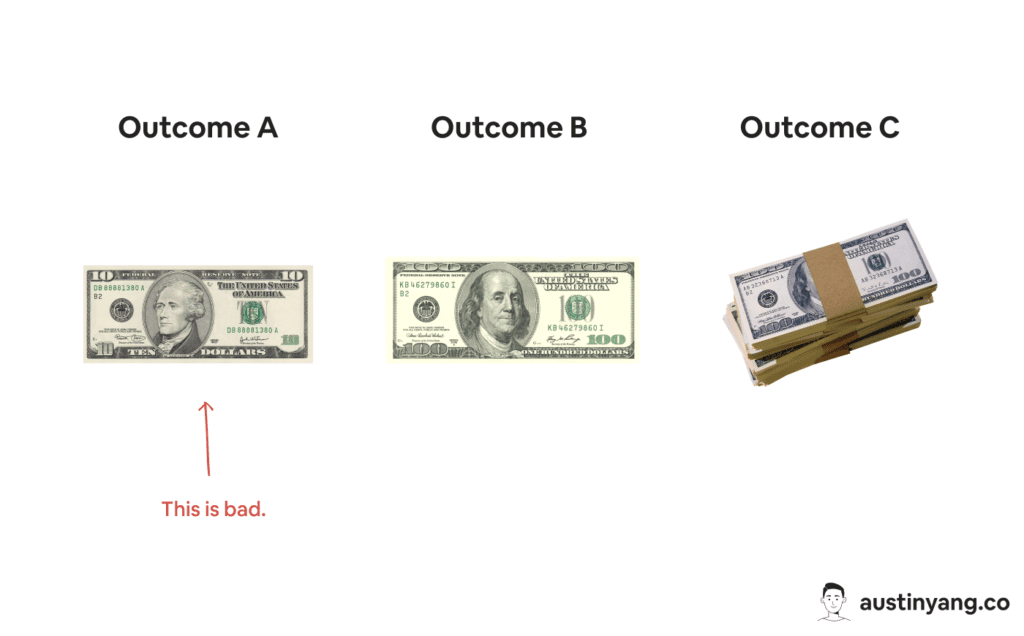

The outcome is relative

The quality of an outcome cannot be judged in absolute terms. You must always consider the opportunity cost.

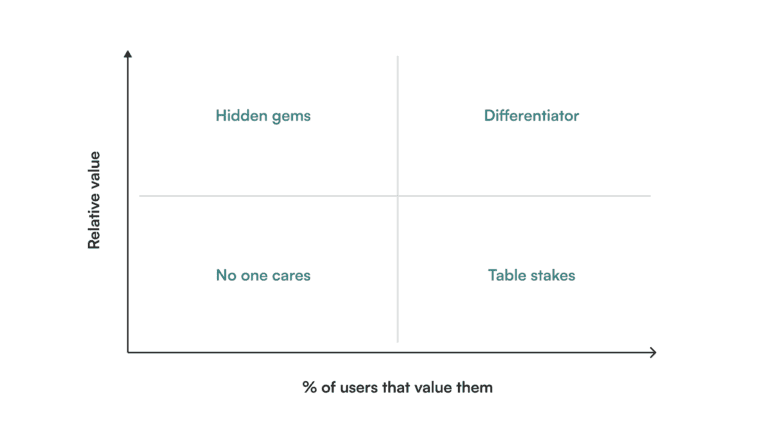

Let’s illustrate it with an example. Say you implemented a strategy that resulted in 2X user growth. You would likely consider it a pretty good outcome, right?

What if I told you that every other option you passed on would have yielded at least 5X growth, and every competitor has grown 10X due to overall market conditions? Would you still think the same?

But here’s the tricky part. You can never know what “could’ve happened” if you had gone with another option.

And no, don’t even bother suggesting controlled experiments. They are rarely possible for complex decisions, and even the most sophisticated experiments conducted in the world of business do not meet the requirement of real science.

As a result, the quality you assign to an outcome is always going to be an educated guess at best (which is often prone to confirmation bias or sunk cost fallacy).

Why is this important?

By knowing what constitute a good decision, we can be more intentional toward making one.

Once we stop measuring a decision solely by its outcome, we get to focus on what we can control: the process and the analysis.

- How is the objective set?

- Who makes the decision?

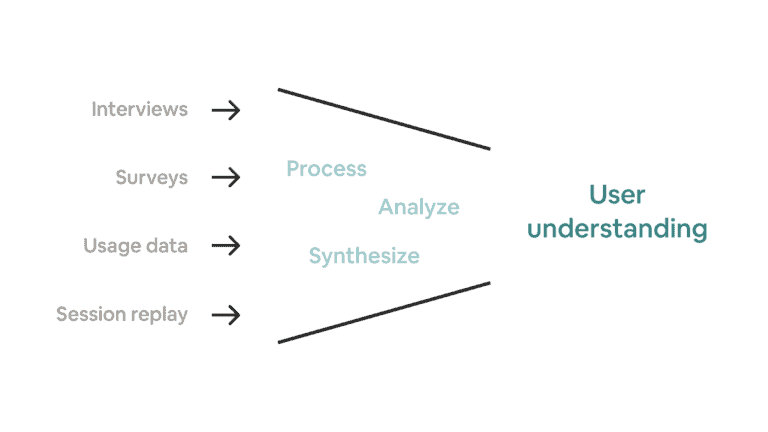

- How do you gather evidence?

- What dimensions have you considered?

- What are their biases?

- How do you piece them together to form a hypothesis?

- What alternative hypotheses have you considered?

- What second-order effects have you considered?

- Is the outcome what we expected?

- Did it happen for the reason we expected?

- What did we learn from it?

These details will unlock far more information than a dumbed-down conclusion like “A is good, B is bad.” They will help you see trade-offs and exam the logic behind each option.

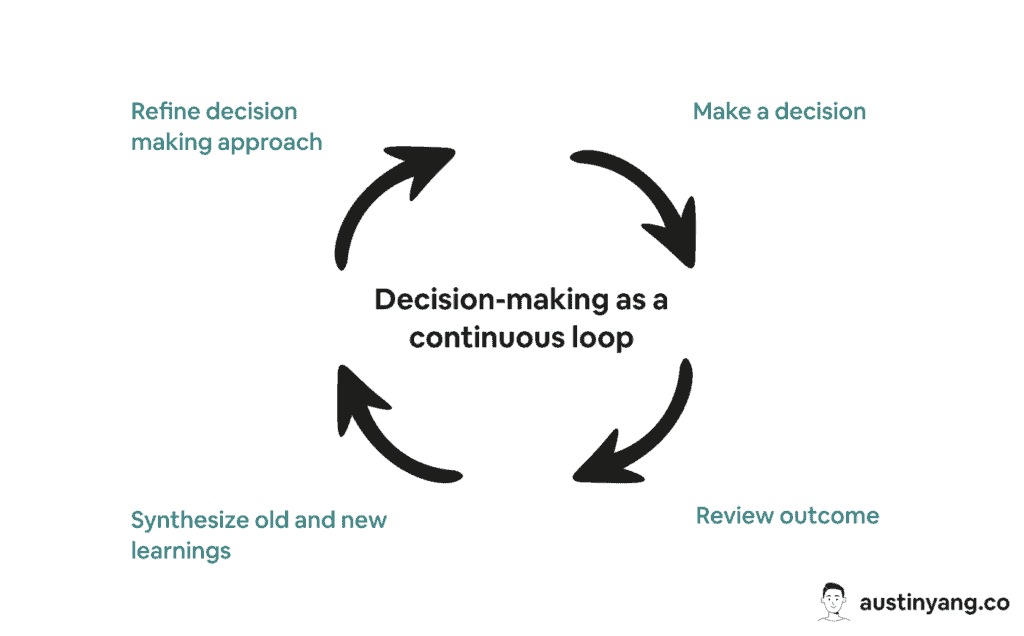

Because no single outcome is definitive, you should treat decision-making as one continuous loop as opposed to independent wins and losses. Every decision is another sample to help you reflect on and refine your approach.

Over time, you will recognize a pattern of what works and what doesn’t — enabling you to make better decisions.

Enjoying this post so far? Subscribe for more.

Indecision is a decision

Although analysis is a good thing, excess analysis that leads to a standstill is not. This is commonly called “analysis paralysis.”

What most people aren’t aware of is that indecision in itself is a decision. You are essentially choosing to stick with the status quo for the time being.

No, I am not suggesting that you should always rush your decisions. I am simply pointing out the implication of not making one.

A quick tip to avoid this trap is to put a timebox into the decision process. Ask yourself, “How long are we willing to stick with the status quo?”

If the decision process reveals that more time is needed, it’s perfectly fine to extend it. But again, be very intentional about whether the delay justifies the value in return. If you find yourself doing this often, ask yourself honestly, “Am I simply bad at estimating the time it takes to make a decision, or am I procrastinating to avoid a potentially bad outcome?”

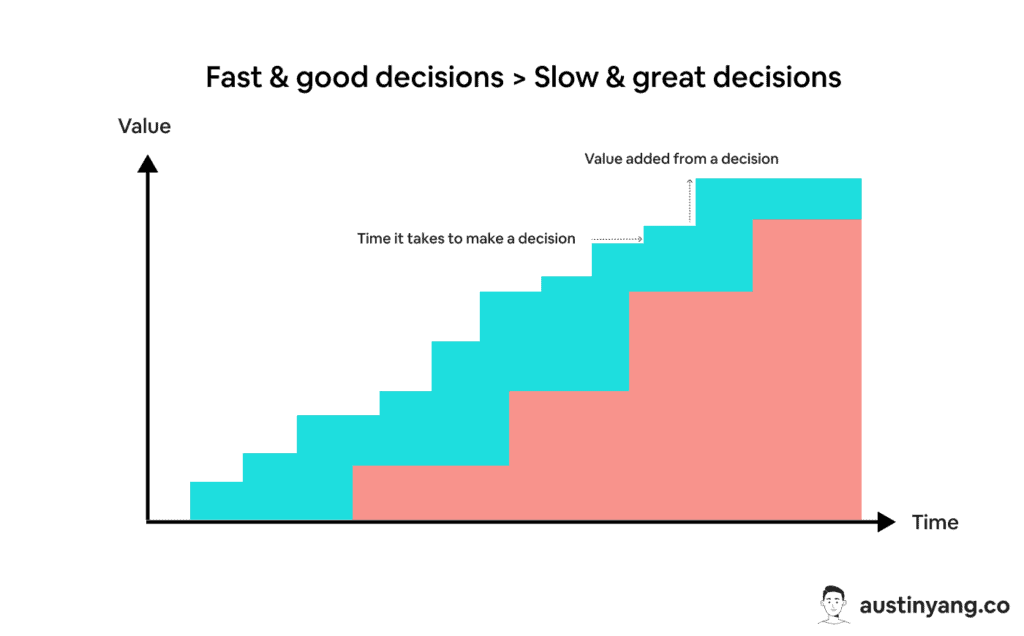

In any given decision, there could be 10 okay options, five good ones, and one or two great ones. If the delta between them isn’t huge, just pick one and go with it.

If you can consistently hit “good” decisions without prolonging decision-making, the speed itself will add up to exceed the benefit of making “great” decisions every single time.

The smartest decision-makers I know — in startups or life — intentionally make rapid “okay’ calls in low-stake situations, so they can allocate more time to decisions that deserve the highest quality.

If you need some help finding the right balance, here are two additional mental models you might find useful:

- Jeff Bezo’s two-way door rule

- A Scorecard: Should a decision be fast, or slow?

- Time value of shipping (every feature is a series of decisions)

Don’t fake decisions

There is one type of decision that doesn’t get talked about enough. These are decisions that get made, but never acted on. I call them “fake decisions.”

Technically speaking, they cannot be called decisions at all. They are simply feel-good exercises to fool yourself into thinking that something has changed.

This is a scenario I’ve personally gone through many times:

“We’re going to shift our focus to segment B.”

“Okay, let’s deprioritize features for segment A.”

“Wait, uh…I mean…I think they will also work for segment B because {insert farfetched reasons}.”

“Revamp our messaging, target SEO keywords, and paid campaign?”

“No…that’d be too risky. We can’t lose this revenue.”

(6 months later) “This strategy didn’t work.”

If you cannot commit to the execution (let’s not even worry about the quality yet), then don’t bother making a decision at all.

Organizational decision-making is an art

Understanding what a good decision looks like is only the first step toward making one. There will always be a degree of subjectivity, and this makes it hard when you are part of an organization.

No matter how scientific your decision-making approach is, getting a team of people to align on all the nuances will always be an art. To put this into practice, you must:

Share the same information: You can’t expect others to understand your decisions if they do not have the same information.

Value diverse views: We all have blind spots. There can only be upsides to taking in more ideas. You don’t have to agree, but you have to listen.

Engage in healthy debates: Assume good intent. Don’t pull rank. Nothing is ever personal.

Reward good analyses over good results: Luck comes and goes, but skills can only improve.

If you are a company leader, the responsibility falls on you to foster good decision-making with concrete processes, feedback, examples, recognition, hiring, and promotions. You can’t count on individual contributors to make good decisions if the incentives aren’t aligned.

Getting good at this as a team is incredibly hard, especially if the team is constantly growing. If after numerous attempts, you still have a hard time aligning on how decisions should be made at the principle level, sometimes parting ways is the best option.

However, if you believe that everyone has the team’s best interest in mind and has the talent to figure it out, perhaps more patience is all you need.

Remember, you don’t have to make perfect decisions (they don’t exist). You just have to make better decisions than you did yesterday.

Special shoutout to Jason Cohen for his valuable feedback on this article.