“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

Every product manager and startup founder has heard of this quote from Henry Ford (did he actually say that?). It’s a perfect example of the Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD) framework — that you should focus on what users need instead of what users want.

While JBTD is indeed a great approach toward building products, too often it gets twisted into “Ignore the solutions users want. If we build a better solution, they will get it. If not, we’ll educate them.”

I’m here to argue that this is a naive idea. You should ask what users want and how they want it. Here’s why —

User needs are complex & not always functional

It might seem obvious that people wanted faster horses to get from point A to point B quicker, but what about safety, comfort, affordability, convenience, social status, the learning curve, their bond with horses, and the fun of riding?

User needs are always more complex than they appear, and they can involve both functional tasks and emotional desires. The latter can be revealed only through what users say (attitudinal research) as opposed to what users do (behavioral research), so it’s essential that you ask.

Some might say: “Then just ask users about their problems, not their desired solutions.”

There are a few limitations with this approach in practice:

- Most people can’t articulate their needs objectively.

- Not every need can be framed as a problem.

For example:

- If you ask a dog owner what problems she has with pet products, she might say, “None, all is good.” —> Because she is thinking about the negative issues that she has experienced.

- But if you ask the same person what she wants, she might tell you, “I would love to have more cute dog costumes!” –> You now know that non-functional dog clothing is at the top of her mind, and you can start exploring the possible motives behind it.

As you can see, a slight change in how you ask the question unlocks a whole new set of information.

Users do offer good ideas

It’s arrogant to assume that users never offer good ideas.

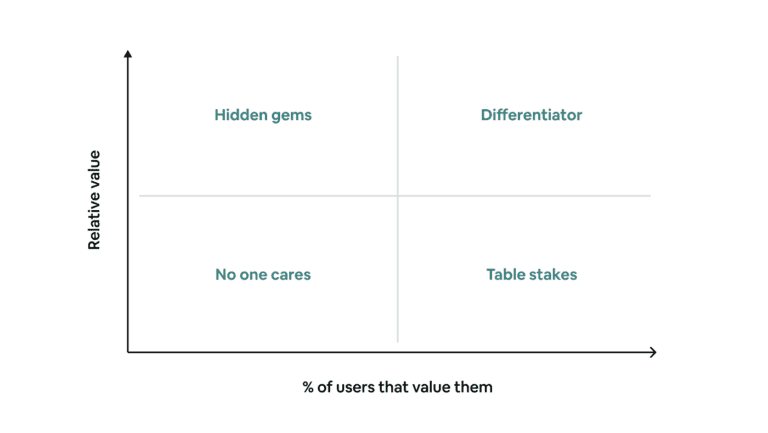

True, 90% of the solutions that users propose are suboptimal, but every once in a while they do make you go, “Wow, that’s brilliant!”

This is especially the case when you serve a niche or complex market. Instead of dismissing user suggestions, leverage your power users to help you navigate the market landscape and generate new ideas.

Of course, don’t expect to apply users’ proposed solutions as-is. It’s your job as a product manager or founder to break them down into usable elements, discover directionally-aligned alternatives, and piece together everything.

Market readiness informs your strategy

Sometimes you understand a problem so deeply that you end up creating a product ahead of the market’s time.

In the best-case scenario, your product will be the first of its kind and gain a first-mover advantage. In the worst-case scenario, your product will end up as one of those “three years too early” stories. Many people will consider this scenario even more devastating than a flat-out failure.

Although no one can predict the outcome 100%, here are three steps you can take to increase your chances of success before building an MVP:

- Ask your target audience what they think is the best solution for the same problem, and why.

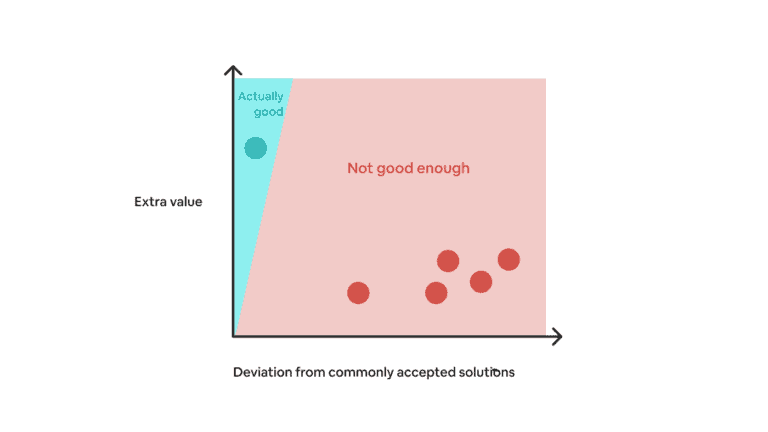

- Then, analyze the gap between their proposals and your solution. Does the gap exist due to technical constraints, social norms, or simply lack of imagination? This helps you gauge market readiness and identify risks.

- Finally, use the insights to shape your positioning, messaging, and GTM strategy, as well as every detail of your product execution.

Note that not every product needs to be “category-defining” like cars or smartphones. In many cases, you can win by offering an incrementally better solution before others do.

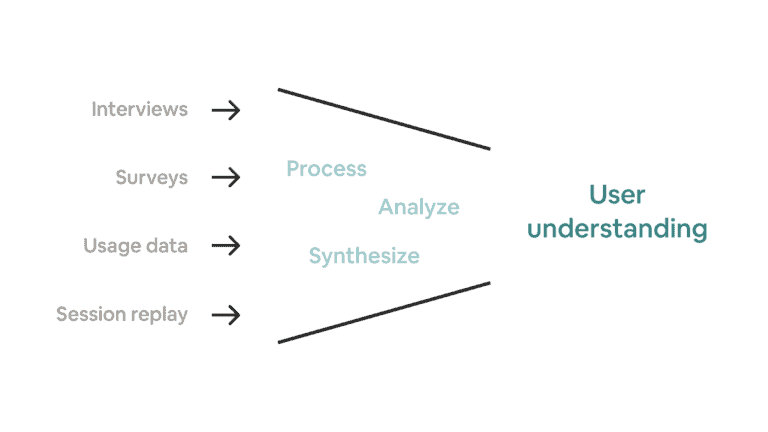

Combine different approaches

User research is like a puzzle. You can see the full picture only when you fit different pieces together — so ask users what they think, observe what they do, conduct interviews, use data, discover problems, and validate solutions.

The point I’m trying to make is that you should not throw one approach out the window because it’s flawed. Instead, understand the pros and cons of different approaches and evaluate how to combine them in each unique context. Don’t be that guy who claims something doesn’t work just because he doesn’t know when or how to use it.

If you want to learn more about user research, I highly recommend that you start with this article by Nielsen Norman Group: